Parasitic Effects in electronic circuit board’s Inductors

Parasitic Effects in electronic circuit board’s Inductors

Although inductance is one of the fundamental properties of an electronic circuit board, inductors are far less common as components than are resistors and capacitors. As for precision components, they are even more rare. This is because they are harder to manufacture, less stable, and less physically robust than resistors and capacitors. It is relatively easy to manufacture stable precision inductors with inductances from nH to tens or hundreds of µH, but larger valued devices tend to be less stable, and large.

As we might expect in these circumstances, electronic circuit board are designed, where possible, to avoid the use of precision inductors. We find that stable precision inductors are relatively rarely used in precision analog circuitry, except in tuned circuits for high frequency narrow-band applications.

Of course, they are widely used in power filters, switching power supplies and other applications where lack of precision is unimportant (more on this in a following section). The important features of inductors used in such applications are their current carrying and saturation characteristics, and their Q. If an inductor consists of a coil of wire with an air core, its inductance will be essentially unaffected by the current it is carrying.

On the other hand, if it is wound on a core of a magnetic material (magnetic alloy or ferrite), its inductance will be nonlinear, since at high currents, the core will start to saturate. The effects of such saturation will reduce the efficiency of the circuitry employing the inductor and is liable to increase noise and harmonic generation.

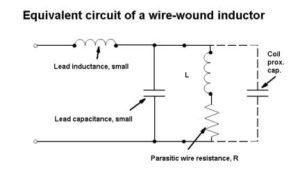

As mentioned above, inductors and capacitors together form tuned circuits. Since all inductors will also have some stray capacity, all inductors will have a resonant frequency

(which will normally be published on their data sheet), and should only be used as precision inductors at frequencies well below this.